Data-driven VC #4: How to scrape alternative data sources?

Where venture capital and data intersect. Every week.

👋 Hi, I’m Andre and welcome to my weekly newsletter, Data-driven VC. Every Thursday I cover hands-on insights into data-driven innovation in venture capital and connect the dots between the latest research, reviews of novel tools and datasets, deep dives into various VC tech stacks, interviews with experts and the implications for all stakeholders. Follow along to understand how data-driven approaches change the game, why it matters, and what it means for you.

Current subscribers: 1,443, +108 since last week

Quick recap: In the last episode, I covered make versus buy for data collection and elaborated on why a hybrid setup is the way to go. Hereof, I shared my database benchmarking study that identifies Crunchbase as the best value for price provider. With this foundation, let’s now explore how we can complement the foundation with further identification and enrichment sources.

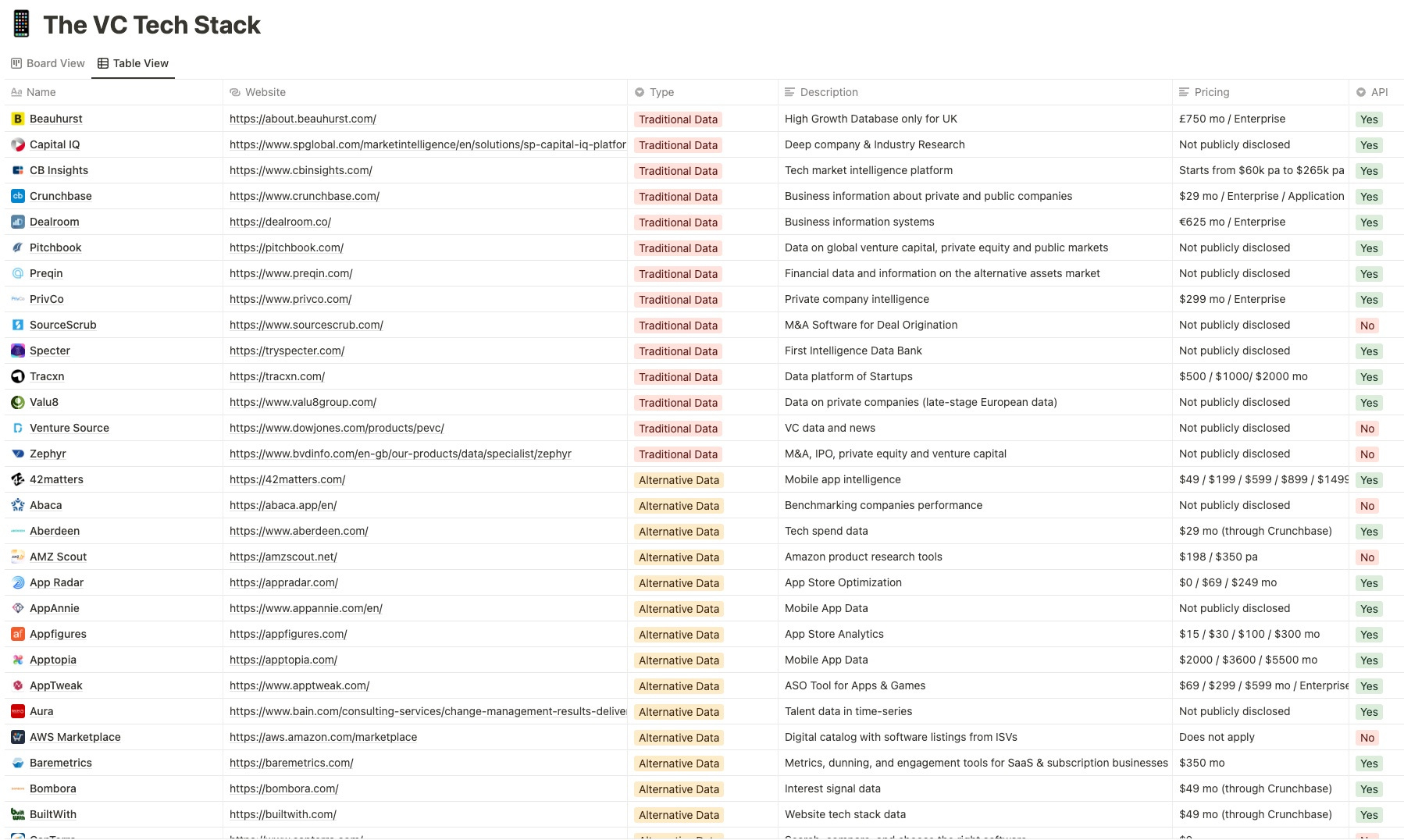

The universe of alternative data sources is sheer endless. Thankfully, my friend Francesco has created a list (screenshot above) and classified all providers into traditional data, alternative data, research, dealflow/CRM systems, matchmaking tools, portfolio management tools, news resources, scouting sources, LP tools, liquidity instruments and infrastructure. Certainly not comprehensive, but a great starting point. With respect to the sourcing and screening stages of the VC value chain, the highlighted providers/websites above are the most relevant ones.

How to get access to alternative data sources?

Let’s start by splitting the alternative data sources into three categories based on their availability (paywall yes/no) and usefulness to scrape (versus just buy):

Paywall and unreasonable to scrape/crawl: Providers in this bucket require a paid subscription but in many cases, the subscription comes along with free data dumps or API access. Even if API access comes at a premium, it’s mostly cheaper than scraping the respective data. Examples include the benchmarked database providers in my previous episode but also alternative sources like SimilarWeb, Semrush or SpyFu. It’s easy to buy them and economically unreasonable to scrape.

Paywall (=private) and reasonable to scrape/crawl: Many providers limit their offering to subscribed users and, in turn, little to no data is available to outsiders. Examples include LinkedIn private profiles (with extended experience, skills, recommendations etc.) that are only accessible via subscriptions like LI Sales Navigator or news providers like TechCrunch, Sifted or Financial Times that hide (parts of) their content behind a paywall.

No paywall (=public) and reasonable to scrape/crawl: This bucket includes all sources that can be accessed without a subscription. Said differently, publicly available data. An easy way to find out if a specific source falls into this bucket is to open your browser in incognito mode, open the website of interest and explore which data you can find without logging in. Examples with high value public data include Github, ProductHunt, LinkedIn public profiles, Twitter or public registers like Handelsregister or Companies House.

Obviously, all data in category 1. should be bought and integrated as a data dump or via an API. The big question mark is rather on categories 2. (private) and 3. (public).

How to scrape/crawl private and public data?

Some terminology upfront: Many people, including myself, use “scraping” and “crawling” interchangeably, but there’s actually a tiny difference: Web scraping is the aimed extraction of specific data from a specific website, whereas web crawling is the aimless collection of any data from a specific website. Linking this to the previous terminology from episode#2, aimless crawling is theoretically more relevant for identification (you never know where an interesting startup might show up, right?) whereas scraping is more relevant for enrichment (you know what you’re looking for).

But anyways, let’s leave the academic nuances aside and jump right in. There are two components of web scraping at scale: the scraping algorithm itself and the execution.

Scraping algorithm (x-axis in the figure below): No need to reinvent the wheel. Many Python packages like BeautifulSoup, Selenium, Scrapy or XPath provide the basic code snippets; see a great post on this here. Stackoverflow and other forums even provide threads that contain the full code for scaping a specific data source. At its core, a scraper emulates human behavior and executes data extraction and button clicks in an automated way. It’s really no rocket science.

Image Source: Frank Andrade, Medium The problem, however, starts as soon as websites change their structure (like moving buttons or text boxes around) and scrapers break. Why? Because the scrapers follow an old logic and search for a button that got moved or is not available anymore. As a result, scrapers manually need to be adopted/mirrored to the new website structure. Easy if it’s just one scraper, but the more scrapers run in parallel, the higher the maintenance effort.

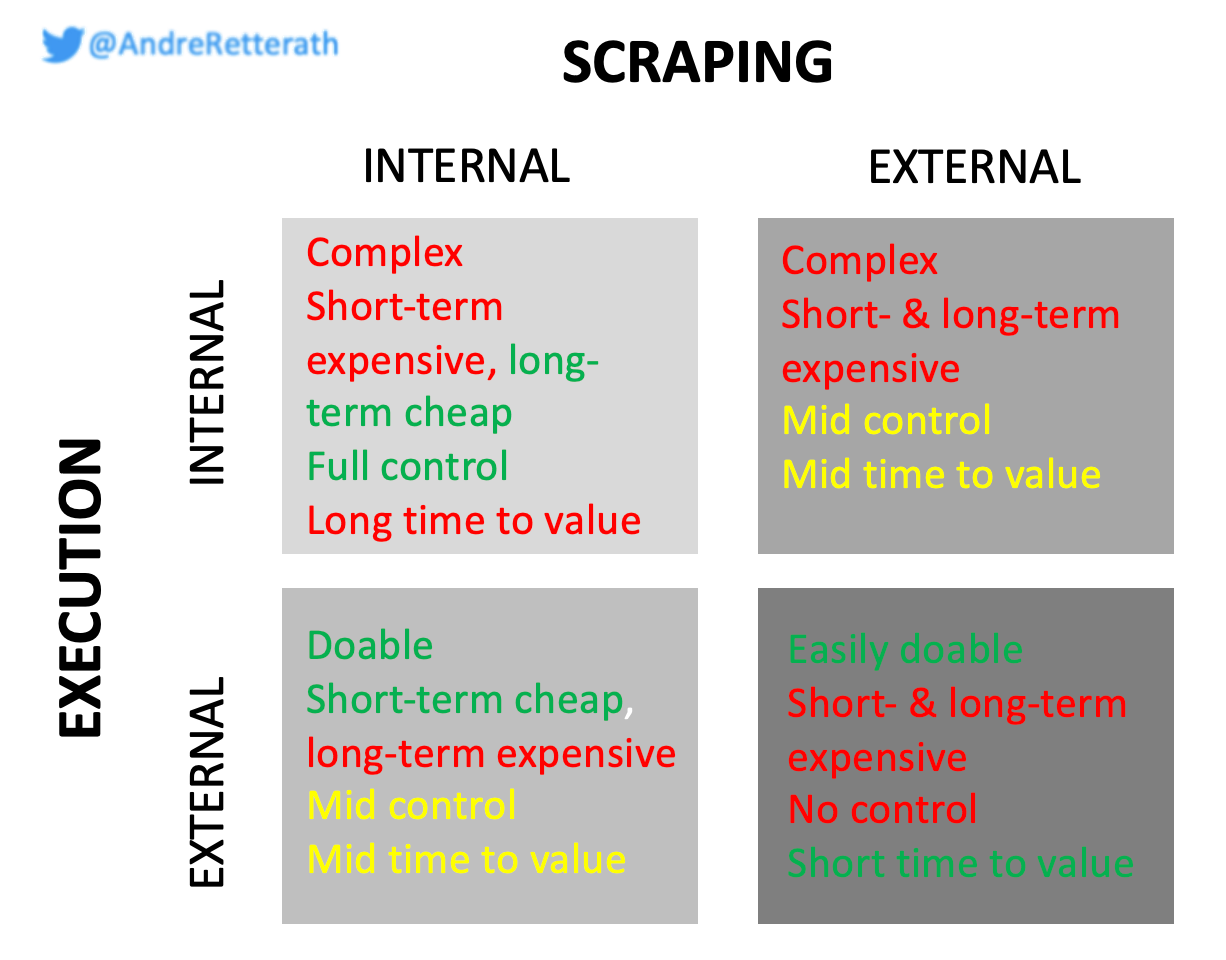

To reduce maintenance efforts, the next level of web scraping is an abstraction logic that removes the need for individual scrapers but allows the application of generic scrapers to every website, independent of their respective structures and resistant to the majority of changes. Here, the internal route (see left two buckets in the figure below) becomes more difficult and, therefore, most people stop at this point and either engage external specialized agencies/freelancers that develop on-demand scrapers (right two buckets in the figure below) or work with external out-of-the-box scraping services like Phantombuster or APIfy (bottom right bucket in the figure below as their full package includes the external execution).

Execution (y-axis in the figure below): Assuming the scraping algorithm works, no matter if internally built or externally via an agency/freelancer, the next big problem is scaling the execution. In fact, this problem is significantly more complex than building the scrapers themselves. To speed up the scraping and further reduce maintenance efforts, there is no way around proxy services. So what’s a proxy?

Proxy is essentially a middleman server that sits between the client and the server. There are many usages for proxies like optimizing connection routes, but most commonly proxies are used to disguise client's IP address (identity). This disguise can be used to access geographically locked content (e.g. websites only available in specific country) or to distribute traffic through multiple identities. In web scraping we often use proxies to avoid being blocked as numerous connections from a single identity can be easily identified as non-human connections.

You can find a great proxy comparison here and read more on the fundamentals here (the quote above is from the same source).

For the scraping algorithm and its execution, there are two options: internal and external. In line with the overall “make versus buy question” in episode#3, we find the same arguments (pro=green, neutral=yellow, con=red) along the dimensions of the complexity of implementation, costs, dependency and time to value.

To keep it hands-on, my preference is to start with external scraping services and focus on category 3. “No paywall and reasonable to scrape” to reduce the time to value and the associated costs. In parallel or right after, build up redundancy by developing proprietary scraping algorithms (yourself or with an external expert freelancer/agency) that follow an abstraction logic, are adaptable to website changes and easy to maintain, and start executing them at a low scale. Increase frequency/volume until you hit the limits. Then look for the right proxy to solve these bottlenecks and scale the execution. Subsequently, replace the respective external scraping services. Repeat the same for category 2. “Paywall and reasonable to scrape”.

With this framework, you’ll get the best of all solutions. Quick wins (easily doable & short time to value) at comparably low cost in the mid-/long-term (high costs only in the beginning; then replaced by an internal solution which is long-term cheaper) with selected external scraping services while at the same time increasing control. So far, so good, but..

.. what’s actually the legal situation around web scraping?

This post is obviously not legal advice, but as many of you have asked me about the status quo, I’m happy to summarize it: Web scraping/crawling is not illegal as long as one does not circumvent a paywall or violate terms and conditions, oftentimes summarized in the robots.txt-file. Moreover, one should avoid collecting personal data or intellectual property, and not sell the data to third parties. A comprehensive write-up on this topic here and the history of prominent web scraping precedents here.

To wrap it up, 2/3 of the VC value is created in the sourcing and screening stages (episode#1). A hybrid solution between make versus buy is most aspiring (episode#3). Crunchbase is a great foundation as it provides the best value for price. Hereof, we add alternative data sources, both for identification and enrichment, as described above.

The next episodes will explore different techniques of how to remove duplicates, link all entities together and make sure our dataset becomes the single source of truth. Moreover, I’ll dive into different classification approaches and feature engineering as a preparation for the screening algorithms, i.e. to cut through the noise.

Stay driven,

Andre

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues and everyone interested in data-driven innovation. Subscribe below and follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter to never miss data-driven VC updates again.

What do you think about my weekly Newsletter? Love it | It's great | Good | Okay-ish | Stop it

If you have any suggestions, want me to feature an article, research, your tech stack or list a job, hit me up! I would love to include it in my next edition😎

Hi Andre,

Love your newsletter. Thank you for your insights and sharing Francesco's awesome list!

I was wondering whether you can elaborate more on your sources/application of non-market data, i.e. more news/media, public policy, etc. These are becoming a crucial success factor for companies. The FT published an article on the importance a few days ago: https://www.ft.com/content/e04bc664-04b2-4ef6-90f9-64e9c4c126aa?sharetype=blocked.

Would love to hear/read your thoughts on that.

Thank you,

Mohamed